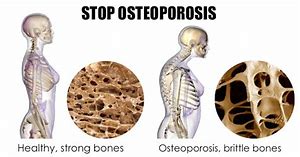

I want you to imagine that you have attended your doctor’s clinic looking for a solution to your annoying menopausal symptoms. During the consultation, the practitioner suggests that as your oestrogen levels are most probably low, it would be a good idea if you undergo a specialised X-ray, known as a DEXA scan, to assess if you are also suffering from low bone density. This sounds totally reasonable and the doctor should be congratulated for conducting preventative medicine. Preventing a reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) and/or treating the condition, could possibly reduce the risk of bone fracture in the future.

Unfortunately, your DEXA scan results arrive, and they are not within the healthy range, i.e. your T score is less than -2.5. Owing to current medical thought that low-trauma fractures are mainly caused by osteoporosis (low BMD), prevention strategies are normally focussed on identification (screening) and bone-targeted pharmacotherapy (Järvinen et al, 2015). Consequently, as a result of your T-scores, your doctor is able to confidently diagnose your condition as Osteoporosis and prescribes you a pharmacological agent such as a bisphosphonate (e.g. Fosomax) or denosumab (e.g. Prolia). You are extremely grateful that this condition has been detected early and religiously take your prescribed medication.

So is this condition really that bad? Will everyone who has been diagnosed with osteoporosis and not taking medication, fracture his or her bones?

Surprisingly, recent research has identified that for women aged 65 years or above, 85% of low-trauma fractures occur in those people who have BMD values above the threshold for osteoporosis diagnosis (i.e. have either osteopenia or even normal bone density) (Curtis et al., 2017; Griffith, 2015; Järvinen et al., 2015). In fact, it has been confirmed that the primary cause of what is considered as osteoporosis fractures (i.e. fracture due to abnormally porous and low-density bones), is rather due to falls as a result of ageing-related decline in general frailty, decreased muscle mass, balance, strength, power, and physical functioning, as well as ailing vision and related modifiable lifestyle factors (Järvinen et al, 2015).

As a result, X-ray screening is unable to identify a large proportion of individuals who will sustain a fracture. Moreover, those patients who have been diagnosed as high fracture risk due to low BMD may never sustain a fracture, as weak bone can survive normal life (Järvinen et al, 2015). Indeed back in 1996, a meta-analysis from 11 studies spanning 9 years and examining 90,999 people and 2000 fractures, found that while bone mineral density measurements could predict fracture risk, it could not identify individuals who will have a fracture, and thus the authors did not recommend a screening program for osteoporosis (Marshall, Johnell & Wedel, 1996). A more effective means of risk evaluation would be if we asked the patient if they had impaired balance. An affirmative answer to this question could predict about 40% of all hip fractures (Järvinen et al, 2015).

While it might sound alarming that approximately 33% of generally healthy individuals aged 65 or above, and 50% of those aged 80 or above, will fall at least once a year, it is comforting to note that only 5% of these falls result in any fracture, and only 1% in a hip fracture (Järvinen et al, 2015).

Treatment

As discussed earlier, the treatment of choice for most doctors for the prevention of hip fractures and other clinic fragility fractures is bone-targeted pharmacological treatment. While osteoporosis may not be the main reason for fractures, these drugs would still appear to be an acceptable form or prevention and treatment if they were effective, inexpensive and with reduced risk of side effects.

Effectiveness:

There has been some positive research showing efficacy of bone-targeted pharmacological treatment in preventing hip fractures and other clinic fragility fractures. Unfortunately though, the experimental groups are usually limited to women aged 65-80 with osteoporosis, with very little or no proof of prevention in men of all ages (30-40% of all hip fractures occur in men) and women over 80 years of age (Järvinen et al, 2015). So it would be wrong to assume that in this latter frail subgroup, pharmacotherapy can reduce fracture risk. Furthermore, existing clinical (real-life) data does not adequately support the anti-fracture (including hip fracture) effects of these drugs (Järvinen et al, 2015).

Another failing of most of the studies are that they have failed to compare the efficacy of these pharmacological agents to individuals of both sexes, in the same age group, who do not have low BMD. Rather the results are extrapolated from estimates derived from younger women. In fact, the T-score estimates from DEXA scans are a measurement of bone mineral density loss of between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations from that of an average young Caucasian adult of approximately 30 years. Such an individual would be at peak bone mass. So would we really expect that the BMD of an 80 year old would be the same as a 30 year old? Would we then say that such an 80 year old would have abnormal bone density because it is lower than a 30 year old? Shouldn’t there normally be some bone loss as we age? We wouldn’t consider wrinkles as a disease, so why do we consider some bone loss as we age as a disease? Unfortunately, that is what is happening currently. Older people are compared with younger people instead of healthy individuals in their own age bracket (which are known as Z-scores). Indeed, when Z-scores are used, the number of people who have the “disease” is drastically reduced. This is illustrated in a 2009 study that compared T- and Z-scores where 30-39% of those subjects who had been diagnosed with osteoporosis were reclassified as either normal or osteopaenic, when Z-scores rather than T-scores were used (Ji, 2017). What’s really interesting is that Z-scores are used for premenopausal women and younger men, and T-scores are used for post-menopausal women and men over 50 (Warriner, & Saag, 2013). Why is that? Why are healthy women, who have suffered no symptoms of low BMD, now being classified as osteoporotic? Could it be that using T-scores for diagnosis could mean more people will need medication, generating billions of dollars of revenue for DEXA scan manufacturers, doctors and pharmaceutical companies? I wonder.

Are the bone drugs safe?

Like most medication, they are not without associated risks. In fact, it has become evident that they are responsible for considerable adverse effects, such as necrosis of the jawbone, and atypical femoral shaft fractures (Järvinen et al, 2015). I find this very ironic. We treat the patients with these medicines to prevent fractures; yet, this is one of the side effects of its use.

To understand the “possible” reason for this, it is first important to know how bone is made and destroyed and how these medications interfere with this process. Normally, bone undergoes remodelling, where old bone is replaced by new bone. Special cells, known as osteoclasts, are recruited to act as a demolition crew and break down old bone to release bone minerals such as calcium and magnesium into the blood and to make room for new bone by the bone building cells, known as osteoblasts. This process of growth and resorption is normally equalised. Hormones, such as oestrogen, are responsible for keeping this process in balance. Bone-targeted pharmacotherapy acts at inhibiting osteoclasts and therefore the breakdown of old bone. The resulting bone is therefore denser, but is it stronger?

Could the outcome of jawbone necrosis and atypical femoral shaft fractures be a result of interfering with the natural turnover of bone, generating a greater proportion of old bone mass? To illustrate this point, think of an old tree branch, which has density but is brittle and easily broken, compared to a young twig that is relatively thin, but malleable and hard to break.

Other consequences of these drugs are gastrointestinal irritation, increased risk of oesophageal cancer, leg cramps, blood clots, nausea and vomiting, vision changes and constipation, to name a few.

Please understand, I am not saying that you should not take medication to prevent bone loss. Like all medication, you should ask your doctor about the side effects and figure out whether the benefits outweigh the risks. This blog, like all my blogs, is meant to inform you, to encourage your own research and challenge you. If after doing your own research you disagree with me, let me know. I am always interested to learn new things.

Alternative Solutions to Reversing Low BMD

Personally, my take on preventing bone fractures is to firstly recognise the early signs of bone loss, such as receding gums; weak and brittle fingernails; decreased grip strength; muscle aches, bone pain; and cramps, height loss and low overall fitness. If you feel that you can identify with these symptoms, then you can make the necessary diet and lifestyle changes that can help you preserve bone. Such modifications would be eating an alkalising whole food diet consisting of lots of fresh fruit and vegetables and eliminating processed foods and sugars, as well as supplementing with adequate calcium, vitamin D, vitamin K, magnesium, manganese, zinc, copper, vitamin C, folate and vitamin B12, and boron. Also ensure that you exercise regularly including both aerobic and weight bearing sets in your daily program, and reduce/eliminate alcohol intake and cigarette smoking.

Take heart. You can rebuild bone at any age.

If you can relate to this article, and need some assistance, please do not hesitate to contact me. Also, if you have still not read my other blogs, please click here. Furthermore, I have a facebook page that not only shares some of my blogs and videos but provides valuable health information. If you gain insight from some of the contributions, don’t forget to click on the “Like” button.

References:

Curtis, E. M., Moon, R. J., Harvey, N. C., & Cooper, C. (2017). The impact of fragility fracture and approaches to osteoporosis risk assessment worldwide. Bone, 104, 29-38.

Griffith, J. F. (2015). Identifying osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 5(4), 592.

Järvinen, T. L., Michaëlsson, K., Jokihaara, J., Collins, G. S., Perry, T. L., Mintzes, B., … & Sievänen, H. (2015). Overdiagnosis of bone fragility in the quest to prevent hip fracture. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 350.

Järvinen, T. L. N., Michaëlsson, K., Aspenberg, P., & Sievänen, H. (2015). Osteoporosis: the emperor has no clothes. Journal of Internal Medicine, 277(6), 662–673. http://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12366

Ji, S. (2017). The Manufacturing of Bone Diseases: The Story of Osteoporosis and Osteopenia. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmedinfo.com/blog/osteoporosis-myth-dangers-high-bone-mineral-density

Marshall, D., Johnell, O., & Wedel, H. (1996). Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. Bmj, 312(7041), 1254-1259.

Warriner, A. H., & Saag, K. G. (2013). Osteoporosis diagnosis and medical treatment. Orthopedic Clinics, 44(2), 125-135.